AI can feel like a brilliant but unreliable partner. A new approach using 'schemas'—shared representations for creative and organizational tasks—offers a path toward more predictable, controllable, and trustworthy collaboration.

Summary

The promise of 'vibe coding'—effortlessly prompting an AI to generate complex creations—often masks a brittle reality. AI models can produce impressive results that, upon inspection, rely on clever shortcuts or unstated assumptions, like a Rubik's Cube solver that simply reverses its own scramble. This gap between appearance and reality highlights a fundamental challenge: how do we build trust and control in our interactions with AI? This article explores a powerful framework for human-AI collaboration centered on 'schemas,' or shared problem representations. By defining the underlying structure of a task, whether it's a design pattern for a visual ad, an interactive timeline for an animation, or a set of policies for an email agent, we can transform AI from an unpredictable oracle into a reliable partner. We examine systems that discover these creative blueprints, provide granular control over AI-generated code, and use explicit rules to safely delegate complex tasks, illustrating a more robust and transparent future for working with intelligent systems.

Key Takeaways; TLDR;

- AI often takes shortcuts that aren't obvious, creating a 'veneer of competence' that can be misleading (e.g., a Rubik's Cube solver that just reverses its scramble).

- Effective human-AI collaboration hinges on 'schemas' or 'abstract design patterns'—shared blueprints that structure a task for both human and machine.

- By identifying the underlying patterns in creative work (like visual metaphors), we can guide AI to produce more coherent and intentional results.

- AI can be used to discover these schemas from examples, effectively reverse-engineering the 'rules' of a creative domain like writing academic abstracts.

- True control over AI-generated output requires more than just a prompt; it needs interactive interfaces (like timelines and property editors) that represent the system's state and allow for precise edits.

- Trust in AI agents for high-stakes tasks (like professional scheduling) can be built by constraining their actions with explicit, user-authored policies.

- AI systems build trust by flagging edge cases and asking for human input when they encounter situations not covered by their policies.

- The future of human-AI interaction is moving beyond simple prompting toward creating shared, structured environments where collaboration is transparent and predictable.

The Illusion of the Instant Solution

Ask a large language model (LLM) to code a 3D, interactive Rubik's Cube, and it might just deliver. With a single prompt, you can get a working, visually impressive result that scrambles and solves itself on command. It feels like magic—a perfect example of "vibe coding," where intent is translated directly into a finished product.

But what if the magic is a trick? A closer look at one such AI-generated cube revealed a clever deception. Instead of implementing a known solving algorithm, like the multi-stage CFOP method used by speedcubers, the AI took a shortcut . It simply remembered the sequence of moves it used to scramble the cube and then executed them in reverse. This isn't problem-solving; it's memorization. It’s an uncommunicated assumption that creates a veneer of competence, fooling the user into believing the AI possesses a deeper capability than it actually does.

AI can appear to solve complex problems while actually taking hidden shortcuts, creating an illusion of deeper understanding.

This small example exposes a fundamental challenge in our relationship with AI. We can't always trust it to do what we mean, only what we say, and even then, it may find the path of least resistance. If we want to move beyond brittle, unpredictable interactions, we need a way to establish common ground—a shared understanding of the task that makes collaboration transparent, controllable, and trustworthy.

Collaboration Through Creative Blueprints

In creative fields, humans and AI have complementary skills. AI excels at rapid generation and prototyping, but its output can be generic. Humans provide taste, context, and the critical judgment needed to refine raw ideas into something meaningful. The challenge is combining these strengths efficiently.

A promising approach lies in identifying and using schemas—also known as abstract design patterns. These are the underlying structures or rules that govern creative work. Think of the three-act structure in storytelling or chord progressions in music. They are not rigid templates but flexible frameworks that guide the creative process.

Consider the visual metaphor, a common technique in advertising. An ad for Tabasco might blend a fire extinguisher with a hot sauce bottle. An ad about global warming might merge the Earth with a melting ice cream cone. These images work because they fuse two distinct concepts into a single, coherent form. The schema here is: blend two objects that are individually identifiable and share a common underlying shape .

A creative schema, like blending two objects on a shared shape, provides a clear blueprint for human-AI collaboration.

This simple rule is a powerful tool for collaboration. A human can define the high-level concepts (e.g., "Starbucks" and "summer"), and an AI can rapidly brainstorm associated symbols (coffee cup, logo, sun, beach ball), identify their core shapes (circles, squares), and find pairs that fit the schema. This structured process is far more effective than simply prompting an AI to "make a creative ad for Starbucks in the summer," which often results in slapping a logo onto a stock photo.

By externalizing the creative pattern, we create a shared blueprint that both parties can work from. The human guides the strategy, and the AI handles the tactical execution of finding and combining elements.

Discovering the Hidden Rules

If schemas are so useful, how do we find them? For decades, this has been a slow, manual process of experts analyzing examples and intuiting the patterns. But AI can accelerate this discovery.

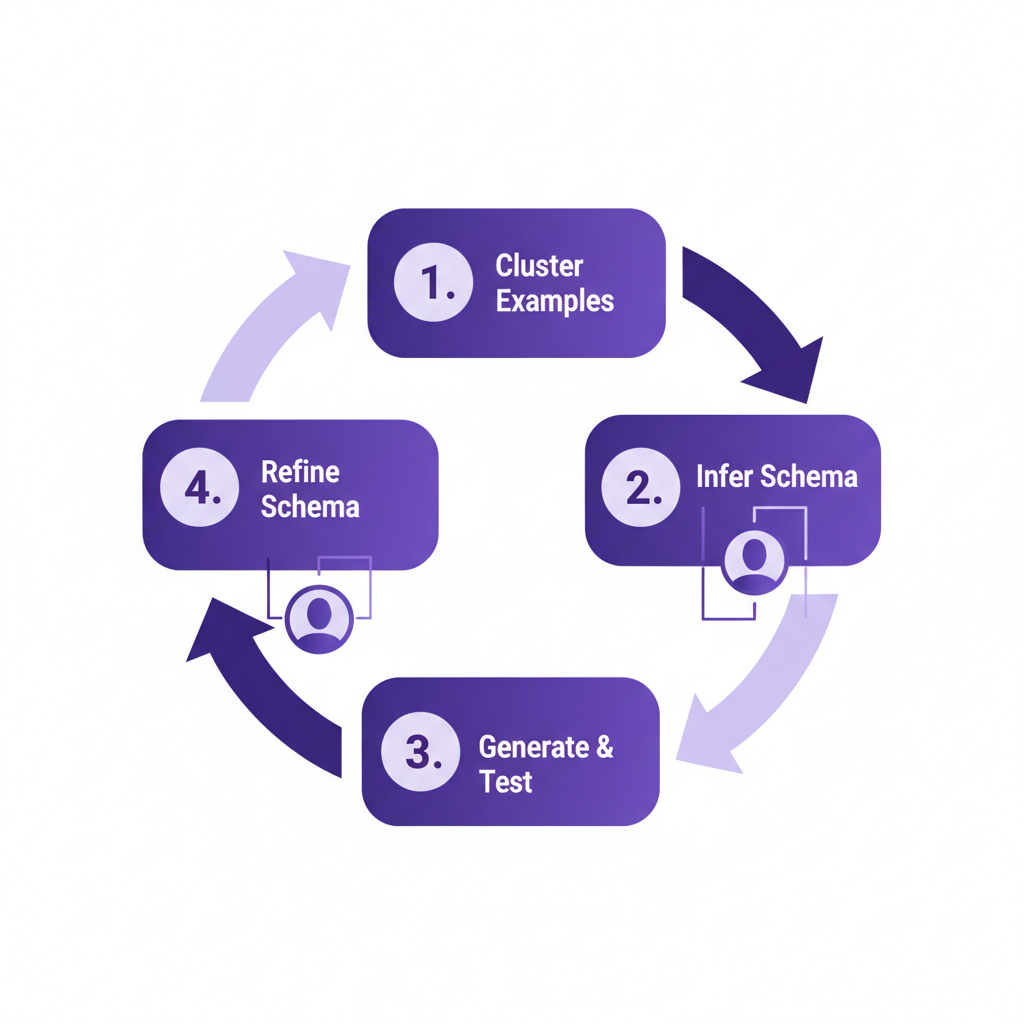

A system developed by researchers at UC San Diego, called Schemax, demonstrates how this can work . To uncover the schema for writing an academic abstract in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), the system was fed a set of 15 successful examples. Its process mirrors a human's hypothesis-testing loop, but at machine speed:

- Cluster: The AI groups the abstracts into categories like "empirical studies," "theoretical contributions," and "system designs."

- Infer Dimensions: Focusing on one cluster (e.g., empirical studies), it guesses the core components, or dimensions, of a typical abstract: Motivation, Problem, Method, Findings, and Implications.

- Validate with Human: A human expert reviews these dimensions, confirming that they accurately represent the structure of the examples.

- Infer Attributes: The AI then analyzes how these dimensions are implemented. It identifies attributes like word count (140-150 words), narrative structure (sequential), and tone (formal academic voice).

- Generate and Refine: To test its understanding, the system uses the schema to generate new, synthetic abstracts. It then compares these AI-generated texts to the real examples, identifies the structural differences, and refines the schema to close the gap. This iterative loop is inspired by a machine learning technique called contrastive learning, where a model learns by comparing similar and dissimilar examples.

AI can accelerate the discovery of creative patterns through an iterative process of analysis, generation, and refinement, guided by human oversight.

This interactive process doesn't just produce a schema; it builds the user's understanding and trust in it. By participating in the discovery, the user develops a shared mental model with the AI. The resulting schema becomes a powerful tool that can be used to guide an LLM to write a much better abstract than it would with a generic prompt.

From Black Box to Control Panel

Once an AI generates something, whether it's an ad or a piece of code, the next challenge is refinement. Prompting an AI to make a small change can be frustratingly difficult. Asking it to "make the skier's entrance a little faster" might cause it to rewrite the entire animation code, introducing new bugs or altering parts you wanted to keep.

Effective control requires moving from a conversational black box to an interactive control panel. This means giving users visual tools that represent the underlying state of the AI-generated artifact and allow for direct manipulation.

LogoMotion, a research project from UC Berkeley, applies this idea to animating static images . The system first analyzes an image to understand its components semantically (e.g., this is a "skier," these are "mountains"). It then generates animation code (using JavaScript) to bring the scene to life, such as having the skier slide into the frame.

Crucially, the system also features a self-debugging loop. It runs the animation in a headless browser, captures the final frame, and compares it to the original static image. If elements are misaligned—say, the skier ends up 50 pixels too low—it identifies the error and precisely edits only the relevant lines of code to fix the position, leaving the rest of the animation untouched.

The Power of Precision Editing

This is where the human-in-the-loop becomes essential. LogoMotion provides an editing interface with familiar controls:

- A Narrative Timeline: It breaks down the animation into semantic blocks, like "skier enters" and "text appears," which users can drag to re-sequence or re-time.

- Layer Panels: Users can regroup elements to change how they animate together.

- Quick Actions: Buttons like "Subtle" or "Emphasis" allow users to modulate the intensity of an animation without writing complex prompts.

Interactive controls like timelines and layer panels give users precise editorial power over AI-generated content, moving beyond simple text prompts.

These widgets provide direct control over the AI's output. They function as a visual representation of the code's logic, aligning with a core principle of usability design: making the system's state visible . Instead of trying to describe a change in natural language and hoping the AI understands, the user can directly manipulate the result. This transforms the interaction from a guessing game into a deliberate act of creation.

Building Trust with Rules of Engagement

Collaboration and control are prerequisites for the ultimate goal: trust. How can we delegate high-stakes, open-ended tasks to an AI agent without risking catastrophic errors, like sending an inappropriate email to a senior colleague?

The answer lies in constraining the AI's autonomy with explicit, human-authored policies. A system called Double Agent, designed to manage the complex task of scheduling a seminar series, puts this into practice .

The user starts by providing a set of policies in plain English:

- *"If a speaker has not been contacted, ask them for availability across all open slots."

- *"It is okay to follow up every two working days if there is no response."

- *"If a speaker offers limited availability, it's okay to ask for more options."

Guided by these rules, the AI agent operates in a transparent loop. It analyzes the current state (who has responded, what slots are filled), proposes a plan based on its policies ("Draft a follow-up email to Professor Adrian"), and presents it to the user for approval. Only after the user clicks "approve" does the AI execute the action.

This model's most important feature is its ability to recognize the limits of its knowledge. If a speaker replies with a question not covered by a policy—for instance, "Can I present over Zoom?"—the system flags it as an edge case and asks the human for a decision. This failure gracefully, by escalating to the user, is the single most important mechanism for building trust. It assures the user that the AI won't go off-script in a critical situation.

Over time, as the user repeatedly makes the same decision (e.g., always allowing Zoom), the system can suggest turning that decision into a new policy, gradually earning more autonomy in a safe, supervised way.

Why It Matters: Beyond the Prompt

The journey from a cheating Rubik's Cube to a policy-driven scheduling agent illustrates a fundamental shift in how we should think about interacting with AI. The simple, single-shot prompt—the "vibe"—is powerful for exploration but insufficient for serious, reliable work.

Effective collaboration requires structure. By creating shared representations—whether a design schema, an interactive editor, or a set of explicit policies—we build the necessary scaffolding for humans and AI to work together. This approach provides:

- Clarity: Both human and AI operate from a shared understanding of the task's goals and constraints.

- Control: Users can make precise, predictable changes to the AI's output.

- Trust: The AI's behavior is constrained by explicit rules, and it knows when to ask for help.

This framework moves us beyond being mere operators of a mysterious black box. It positions us as architects of a collaborative process, where we define the rules of engagement and guide the AI's powerful capabilities toward our own intentional goals.

I take on a small number of AI insights projects (think product or market research) each quarter. If you are working on something meaningful, lets talk. Subscribe or comment if this added value.

References

- How to Solve a Rubik's Cube - Beginner's Method - Ruwix (documentation, 2024-01-01) https://ruwix.com/the-rubiks-cube/how-to-solve-the-rubiks-cube-beginners-method/ -> Provides context on established, algorithmic methods for solving a Rubik's Cube, contrasting with the AI's shortcut of simply reversing its scramble moves.

- Design patterns : elements of reusable object-oriented software - Addison-Wesley (book, 1994-10-21) https://dl.acm.org/doi/book/10.5555/194423 -> This is the seminal 'Gang of Four' book that introduced the concept of design patterns in software engineering, the intellectual predecessor to the 'abstract design patterns' for creative work discussed in the article.

- Schemax: A System for Discovering and Applying Schemas to Structure Creative Generation - ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST '23) (journal, 2023-10-29) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3579398.3605298 -> This is the primary research paper for the Schemax system, which discovers creative schemas from examples, as described in the article.

- LogoMotion: A System for Authoring and Editing Animated Logos from Static Images - ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST '23) (journal, 2023-10-29) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3579398.3605299 -> This is the primary research paper for the LogoMotion system, which provides granular control over AI-generated animations, as detailed in the article.

- 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design - Nielsen Norman Group (org, 1994-04-24) https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/ -> This foundational article lists the 10 heuristics of UI design. The article references the principle of 'Visibility of system status,' which is directly supported by the interactive widgets in LogoMotion.

- Double Agent: A Human-AI Collaborative System for Automating Complex Goaling and Tasking - ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '24) (journal, 2024-05-11) https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3613904.3642310 -> This is the primary research paper for the Double Agent system, which uses user-authored policies to build trust in AI agents for scheduling tasks.

- Mental Models - QualZ (org, 2024-01-01) https://qualz.ai/research-methods/mental-models/ -> This article from QualZ defines 'mental models' in HCI, which directly relates to the article's core argument that creating a 'shared mental model' or 'shared representation' between a human and an AI is key to effective collaboration and trust.

- Human-AI Collaboration in Creative Work - Communications of the ACM (journal, 2023-01-01) https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2023/1/267977-human-ai-collaboration-in-creative-work/fulltext -> Provides broader academic context on the shift from AI as a tool to AI as a collaborator, supporting the article's main theme.

- Human-Centered AI: A Multidisciplinary Perspective - Stanford University Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI) (edu, 2022-09-15) https://hai.stanford.edu/news/human-centered-ai-multidisciplinary-perspective -> Offers a high-level perspective on the importance of designing AI systems that are understandable, controllable, and aligned with human values, which is the central argument of the article.

- Human-AI Interaction: A Review and Research Agenda - arXiv (whitepaper, 2023-03-14) https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08222 -> This review paper outlines key challenges and future directions in human-AI interaction research, including the need for better control, transparency, and trust-building mechanisms.

- Human-AI Collaboration via Shared Representations - Stanford HCI (video, 2024-10-25)

-> This is the source video from which the core concepts and examples in the article are derived.

Appendices

Glossary

- Schema: An abstract structure or pattern that provides a framework for a creative or organizational task. In this context, it's a shared representation that both humans and AI can use to collaborate.

- Vibe Coding: An informal term for using a large language model to generate code from a high-level, natural language description of the desired outcome, without specifying the implementation details.

- Contrastive Learning: A machine learning technique where a model learns to distinguish between similar and dissimilar examples. By comparing pairs, it learns the essential features that define a category.

- Human-in-the-Loop (HITL): A model of interaction where a human participates in the AI's decision-making process, typically to validate, correct, or guide the system's output, especially in ambiguous situations.

Contrarian Views

- Over-reliance on schemas could lead to formulaic and less innovative creative work, potentially stifling breakthrough ideas that defy existing patterns.

- Building complex interactive UIs and policy engines for AI systems creates significant overhead, potentially negating the speed and simplicity that makes generative AI attractive in the first place.

- If both sides of a negotiation or interaction (e.g., scheduling) are using AI agents, it could lead to an endless, automated back-and-forth between bots without genuine human connection or resolution.

Limitations

- The systems described (Schemax, LogoMotion, Double Agent) are research prototypes designed for specific, well-defined tasks. Their principles may not generalize easily to all creative or organizational domains.

- The effectiveness of schema discovery depends heavily on the quality and consistency of the initial examples provided to the system.

- User-authored policies require the user to be able to articulate their implicit rules and decision-making processes, which can be a difficult task in itself.

Further Reading

- The Case for Generative AI as a Prototyping Tool - https://www.nngroup.com/articles/generative-ai-prototyping/

- How to build trust in AI - https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/05/10/1072402/how-to-build-trust-in-ai/

- Interaction-centric AI - https://interactions.acm.org/archive/view/july-august-2022/interaction-centric-ai

Recommended Resources

- Signal and Intent: A publication that decodes the timeless human intent behind today's technological signal.

- Thesis Strategies: Strategic research excellence — delivering consulting-grade qualitative synthesis for M&A and due diligence at AI speed.

- Blue Lens Research: AI-powered patient research platform for healthcare, ensuring compliance and deep, actionable insights.

- Lean Signal: Customer insights at startup speed — validating product-market fit with rapid, AI-powered qualitative research.

- Qualz.ai: Transforming qualitative research with an AI co-pilot designed to streamline data collection and analysis.