Generative AI is more than a tool for creating images and text. Its core principles are deeply rooted in physics, and its future lies in becoming both a precise instrument for science and a dynamic partner for art.

Summary

Generative AI's creative prowess is well-known, but its deepest innovations are emerging from an unlikely conversation between physics, music, and computer science. This article explores the 'virtuous cycle' where fundamental scientific principles inspire more powerful AI architectures, which in turn are used to solve intractable problems in science. We examine how diffusion models for image generation are rooted in the physics of ordinary differential equations, and how researchers are accelerating them by orders of magnitude. We then turn to the stringent demands of theoretical physics, where AI models must be 'asymptotically exact'—not just plausible, but provably correct—to simulate the building blocks of matter. This requires encoding complex symmetries and handling inverted data hierarchies, pushing AI into new territory. Finally, we see a different kind of partnership emerge in music, where AI transforms from a static generator into a real-time improvisational partner, learning the grammar of human collaboration. Together, these fields reveal a future where AI is not a monolithic tool, but a specialized collaborator, tailored for the precision of science and the fluidity of art.

Key Takeaways; TLDR;

- Many successful generative AI models, like diffusion models, are directly inspired by concepts from physics, such as diffusion processes and ordinary differential equations (ODEs).

- Researchers are developing novel techniques to 'fast forward' the slow, step-by-step process of AI generation, enabling near-instant results by learning to solve the underlying ODEs in a single step.

- When applied to scientific problems like quantum field theory, AI models face a much higher bar than in creative fields; they require 'asymptotic exactness' to ensure their solutions are mathematically correct, not just plausible.

- Scientific applications present unique challenges for AI, including an 'inverted data hierarchy' (vastly more features than samples) and the need to hard-code fundamental symmetries of nature into the model's architecture.

- This interplay creates a 'virtuous cycle': physics challenges drive AI innovation, and these new, more robust AI models help accelerate scientific discovery.

- In creative fields like music, the frontier of AI is moving from static generation to real-time, interactive collaboration.

- Developing a musical 'jambot' requires solving complex human-computer interaction problems, such as coordination, turn-taking, and establishing a two-way communication channel between the musician and the AI.

- The future of AI is not one-size-fits-all; it involves creating specialized models that are principled and precise for science, and interactive and adaptive for art. Generative AI has captured the public imagination as a creator of fantastical images and surprisingly fluent text. But behind the curtain of these creative tools, a deeper, more fundamental conversation is taking place—one that connects the abstract world of theoretical physics, the improvisational flow of music, and the core architecture of artificial intelligence. This interplay is creating a “virtuous cycle”: scientific principles inspire more powerful AI, and in turn, these advanced AI models are becoming indispensable tools for scientific discovery and artistic partnership.

This isn't just about AI for science or AI for art. It's about a reciprocal relationship where the challenges in one domain forge the breakthroughs in another, revealing a future where AI is not a single, monolithic entity but a diverse ecosystem of specialized collaborators.

The challenges in fundamental science and interactive art are driving the next wave of AI innovation.

From Physical Laws to Generative Code

Many of today's most successful generative models, particularly the diffusion models that power image generators like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, are deeply rooted in the language of physics. At its core, a generative model learns to map one distribution of data to another. Imagine a vast, abstract space where every possible noisy, static-filled image exists. In another space, every possible coherent, realistic image exists. The goal of the AI is to build a bridge, a function that can take any point from the noise space and transform it into a meaningful image.

The inspiration for how to build this bridge comes from a classic physical process: diffusion. As computer scientist Kaiming He explains, think of dropping a speck of ink into a glass of water. Over time, the ink particles diffuse, spreading out randomly until they are evenly distributed. Diffusion models replicate this process digitally. They start with a clean image (the ink drop) and systematically add noise step-by-step until all that remains is static (the diffused water).

To generate a new image, the model simply learns to reverse this process. It starts with random noise and, step by painstaking step, removes it, following a learned trajectory back toward the space of coherent images. Mathematically, this trajectory is described by an Ordinary Differential Equation, or ODE—a type of equation used throughout physics to model systems that change over time, from planetary orbits to fluid dynamics.

The Need for Speed: Fast-Forwarding Reality

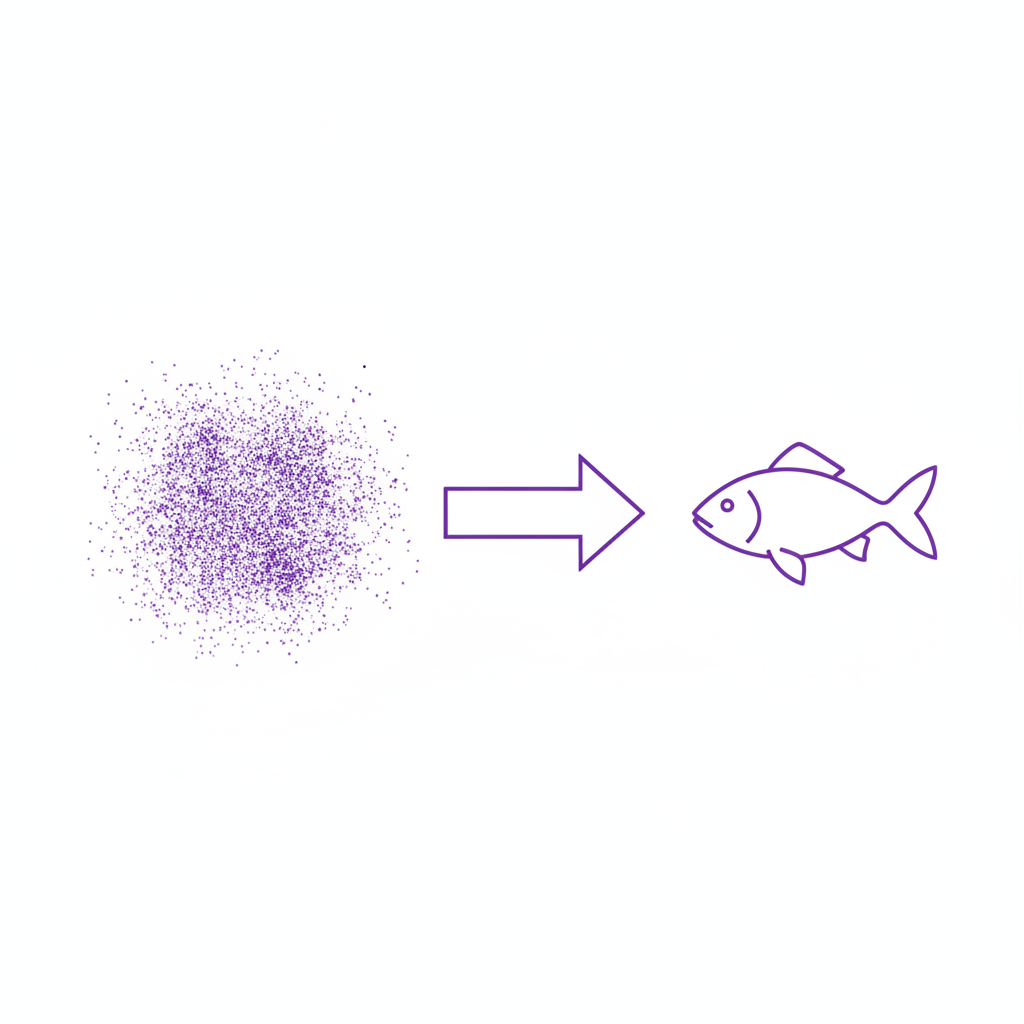

The major drawback of this physics-based approach is its speed. Solving the ODE requires hundreds or even thousands of small steps, each demanding a massive computation from a neural network. This is why early diffusion models took minutes to generate a single image. The challenge, then, was to find a way to solve the equation without taking every single step along the path.

Recent work has focused on creating a kind of computational shortcut. Instead of calculating the velocity of the transformation at every point in the trajectory, researchers are training a second neural network to learn the average velocity needed to get from the starting point (noise) to the endpoint (image) in a single leap. As He describes it, this “fast forward” model can jump across the entire trajectory at once.

Interestingly, the resulting image isn't identical to one produced by the slow, step-by-step method. While it preserves the high-level, macroscopic properties—a fish is still a fish of the same species and pose—the low-level details like the exact pattern of its fins or the bubbles in the background will differ. This trade-off is a feature, not a bug. The model maintains semantic accuracy while allowing for fine-grained variation, a property that turns out to be incredibly useful when applying this same logic back to scientific problems.

Generative models can learn to reverse the process of diffusion, turning random noise into a coherent image in a single computational leap.

When 'Good Enough' Isn't Good Enough: The Demand for Exactness

This ability to generate plausible, high-level results is perfect for creative applications. But in the world of fundamental physics, “plausible” is dangerously insufficient. As theoretical physicist Phiala Shanahan explains, when using AI to solve the equations that govern the universe, there is no room for approximation. The answer must be exact. [4, 12]

Shanahan’s work reframes the very idea of generation. A physical system, she argues, is itself a generative model. The collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, for example, are a physical process that generates data observed in detectors. Her research in lattice quantum chromodynamics (QCD) involves calculating the properties of matter from the ground up—starting with the fundamental equations describing quarks and gluons. [10, 23] These calculations are expressed as complex integrals, which can be solved by sampling points from a known probability distribution.

Here, the task for a generative AI is not to create a beautiful image but to generate samples from a probability distribution with perfect fidelity. This requirement is known as asymptotic exactness. “If I'm solving an integral and the answer is 2, I had better get 2 no matter what I do to solve my equation,” Shanahan notes. An AI model in this context must be constructed so that even if it’s poorly trained, it will still produce the correct answer, just much more slowly. The goal of training is to make it faster, not more correct. This is a profound departure from the goals of mainstream generative AI.

The Unique Challenges of Scientific AI

This demand for precision imposes unique and formidable challenges that push AI development in new directions.

First, scientific data often has an inverted data hierarchy. An image dataset might contain billions of examples (samples), each described by a few million pixels (features). In quantum field generation, the situation is flipped: researchers may only have a few thousand precious samples, but each one is described by an astronomical number of degrees of freedom—sometimes as high as 10¹².

Second, these models must respect the fundamental symmetries of nature with perfect precision. One such example is gauge symmetry, a complex internal symmetry in particle physics. It dictates that two configurations of a quantum field that look wildly different at the level of individual data points are, from a physics perspective, exactly the same and must be generated with identical probability. These aren't soft preferences that can be learned from data; they are hard constraints that must be built into the AI’s architecture from the ground up.

Meeting these demands has led to the development of novel, physics-informed AI architectures, such as flow-based models that can guarantee exactness and incorporate complex symmetries. This is the virtuous cycle in action: the intractable problems of physics force the invention of more robust, principled AI, which then unlocks new scientific discoveries. [32, 36]

Unlike creative AI, models for physics must perfectly respect fundamental symmetries, like the gauge symmetry of a quantum field.

From Precise Equations to Improvised Duets

If physics demands precision and exactness from AI, music asks for something else entirely: partnership and interactivity. The focus shifts from finding a single correct answer to engaging in a fluid, real-time dialogue. This is the world explored by composer and AI researcher Anna Huang, whose work traces the evolution of AI from a static content generator to a live improvisational partner. [6, 7]

Huang was one of the researchers behind Music Transformer, an early and influential adaptation of the Transformer architecture for music generation. [8, 9] By using the self-attention mechanism, the model could capture the long-range patterns and self-references that give music its structure, generating compelling piano pieces. But generating a static piece in a lab is one thing; performing live on stage with a human musician is another.

This ambition led to the development of a “jambot”—an AI agent designed for real-time musical improvisation. The project immediately surfaced a host of challenges that have less to do with model architecture and more to do with human-computer interaction. How do you coordinate on the fly? How do you trade solos? How do you avoid stepping on each other's toes—or, in this case, playing in the same register of the piano and creating a muddy sound?

The Grammar of Collaboration

Early experiments revealed the AI, trained on solo piano music, tended to dominate the middle of the keyboard, forcing its human partner to play only with one hand at the extremes. The initial interaction was a fight for space, not a collaboration.

The solution was to build a system for two-way communication. The human musician was given controls to guide the AI, for instance, by telling it to play in a higher or lower register or to play more sparsely. Crucially, the communication flowed both ways. The model would signal its intentions back to the musician, creating a feedback loop that allows for mutual adaptation. [1, 14]

This work transforms the AI from a tool that responds to a prompt into an agent with a degree of autonomy. It has to listen, anticipate, and respond, all within the unforgiving tempo of a live performance. The goal is not just to generate music that sounds good, but to build a system that a musician feels they have a genuine partnership with. It’s a shift from prompt-and-response to a co-creative dialogue.

The frontier of creative AI is moving from static generation to interactive partnership, requiring a new language of collaboration.

Why It Matters: A New Generation of AI

The parallel journeys of AI in physics and music reveal a crucial insight about the future of the technology. The quest for a single, all-powerful general AI often misses the point. The most exciting innovations are happening at the intersection of disciplines, where the unique demands of a specific field force us to build new kinds of AI.

Physics demands models that are provably correct, deeply structured, and capable of handling bizarre data landscapes. Music demands models that are interactive, responsive, and fluent in the unspoken language of human collaboration. One pushes for rigor and exactness; the other for fluidity and agency.

Together, they paint a picture of a more mature, diverse AI ecosystem. The principles of physics that helped create today's image generators are now being refined by the extreme demands of fundamental science. At the same time, the interactive needs of artists are pushing AI beyond static generation and toward true partnership. The conversation between these fields is not just an academic curiosity—it is the engine driving the next generation of artificial intelligence.

I take on a small number of AI insights projects (think product or market research) each quarter. If you are working on something meaningful, lets talk. Subscribe or comment if this added value.

References

- Designing Live Human-AI Collaboration for Musical Improvisation - Generative AI and HCI - ACM (journal, 2024-05-11) https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3613904.3642578 -> This paper details the design of systems for real-time musical improvisation between humans and AI, discussing the challenges of coordination and the need for interfaces that support co-performance, directly related to Anna Huang's work.

- The Virtuous Cycle of AI and Physics - NSF AI Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Fundamental Interactions (IAIFI) (whitepaper, 2023-09-20) https://www.iaifi.org/virtuous-cycle -> This white paper, mentioned by Phiala Shanahan, outlines the feedback loop between physics and AI, where challenges in physics drive AI innovation and vice-versa. It's a foundational source for the article's central theme.

- DPM-Solver: A Fast ODE Solver for Diffusion Probabilistic Model Sampling in Around 10 Steps - arXiv (whitepaper, 2022-06-02) https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.00927 -> This paper presents a method for dramatically speeding up diffusion model sampling by creating a dedicated high-order ODE solver, which corroborates Kaiming He's discussion of 'fast-forwarding' the generation process.

- Machine learning for sampling high-dimensional probability distributions in lattice field theory - Princeton University (talk, 2023-11-15) https://physics.princeton.edu/events/machine-learning-seminar-phiala-shanahan-mit-machine-learning-sampling-high-dimensional -> An abstract for a talk by Phiala Shanahan covering the core topics she discusses in the video: flow-based models, guarantees of exactness, and incorporating symmetries for lattice quantum field theory.

- Generative AI is accelerating the pace of change in scientific computing research - NVIDIA Technical Blog (news, 2023-05-26) https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/ai-for-a-scientific-computing-revolution/ -> Provides context on the broader trend of using generative AI for scientific computing, including in physics, which supports the article's claims about AI's growing role in science.

- Anna Huang - MIT Music and Theater Arts - MIT (org, 2024-11-01) https://mta.mit.edu/people/anna-huang/ -> Confirms Anna Huang's position at MIT and her research focus on human-AI partnerships in music-making, and her creation of Music Transformer. This verifies the identity of the third speaker.

- A model of virtuosity - MIT News (news, 2024-11-19) https://news.mit.edu/2024/model-virtuosity-jordan-rudess-1119 -> This article describes the 'jambot' project at MIT, explicitly mentioning Anna Huang's Music Transformer as the starting point and detailing the collaboration with musicians, providing direct evidence for the music section.

- Music Transformer: Generating Music with Long-Term Structure - arXiv (whitepaper, 2018-09-12) https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.04281 -> The original paper for Music Transformer, co-authored by Anna Huang. It establishes the technical foundation for her work on applying Transformers to music.

- AI Song Contest: Human-AI Co-Creation in Songwriting - ISMIR (journal, 2020-10-11) https://archives.ismir.net/ismir2020/paper/000028.pdf -> A paper co-authored by Anna Huang that studies the challenges and needs of musicians co-creating songs with AI, providing academic backing for the discussion on human-AI interaction in music.

- Phiala E. Shanahan - Faculty Page - MIT Physics (org, 2024-01-01) https://physics.mit.edu/faculty/phiala-shanahan/ -> Provides biographical information and a summary of Prof. Shanahan's research, confirming her focus on lattice QCD and the application of machine learning to nuclear and particle physics.

- Generative AI and simulation modeling: how should you (not) use large language models like ChatGPT - System Dynamics Review (journal, 2024-07-22) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sdr.1777 -> Discusses the broader applications and guidelines for using generative AI in scientific simulation, providing context for the ideas presented by He and Shanahan.

- Opaque AI research tools could undermine trust and accuracy of scientific findings - The Royal Society (org, 2024-05-28) https://royalsociety.org/news/2024/05/science-in-the-age-of-ai-report/ -> This report highlights the challenges of using 'black box' AI in science, underscoring the importance of the 'exactness' and interpretability that Shanahan's work strives for.

- Generative AI, Physics, and Music - MIT EECS (video, 2024-10-27)

-> The original source presentation for the article's core ideas.

Appendices

Glossary

- Diffusion Model: A type of generative model that learns to create data, such as images, by reversing a process of gradually adding noise. It starts with random noise and refines it step-by-step into a coherent output.

- Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE): A mathematical equation that describes how a system changes over time. In diffusion models, it defines the 'path' from a noisy input to a clean output.

- Asymptotic Exactness: A requirement in scientific AI that the model must converge to the mathematically correct solution, especially with more data or computation. It prioritizes correctness over mere plausibility.

- Lattice Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD): A computational method used in theoretical physics to study the strong force that binds quarks and gluons together into protons and neutrons. It involves simulating particle interactions on a discretized grid of spacetime.

- Gauge Symmetry: A fundamental principle in particle physics stating that certain changes to the underlying fields of a system do not alter the physical outcome. AI models for physics must be built to respect these symmetries perfectly.

- Transformer: A neural network architecture based on the 'self-attention' mechanism. It excels at handling sequential data like text or music by weighing the importance of different parts of the input sequence.

Contrarian Views

- The reliance on complex, 'black box' AI models in science could undermine the reproducibility and trustworthiness of scientific findings if their outputs cannot be fully explained or verified.

- While AI can accelerate simulations, it may struggle with true scientific discovery that requires logical inference, abstraction, and forming novel hypotheses from incomplete information.

- The promise of human-AI creative partnership can be overstated; current systems often require significant human guidance, curation, and control to produce high-quality, meaningful artistic output.

Limitations

- The 'fast-forward' methods for diffusion models are an active area of research; they often involve a trade-off between speed and the fine-grained quality or diversity of the generated samples.

- Building physics-informed AI that is asymptotically exact and respects all necessary symmetries is extremely difficult and currently limited to specific sub-fields of physics.

- Real-time interactive AI for music is computationally expensive and highly sensitive to latency, making it challenging to deploy outside of controlled lab and concert settings.

Further Reading

- The NSF AI Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Fundamental Interactions (IAIFI) - https://www.iaifi.org/

- What are Diffusion Models? - https://www.qualcomm.com/developer/research-papers/technical-deep-dive-what-are-diffusion-models

- Magenta: Make Music and Art Using Machine Learning - https://magenta.tensorflow.org/

Recommended Resources

- Signal and Intent: A publication that decodes the timeless human intent behind today's technological signal.

- Thesis Strategies: Strategic research excellence — delivering consulting-grade qualitative synthesis for M&A and due diligence at AI speed.

- Blue Lens Research: AI-powered patient research platform for healthcare, ensuring compliance and deep, actionable insights.

- Lean Signal: Customer insights at startup speed — validating product-market fit with rapid, AI-powered qualitative research.

- Qualz.ai: Transforming qualitative research with an AI co-pilot designed to streamline data collection and analysis.